Imagine a creature that can generate enough electricity to power a small appliance or stun a predator with a single jolt. This isn't science fiction; it's the incredible reality of organisms equipped with The Electrogenic Cells (Electrocytes) and Their Function. These specialized cells are nature's living batteries, capable of producing powerful electrical discharges that have fascinated scientists and inspired technological innovation for centuries.

From shocking prey to navigating murky waters, electrocytes are a testament to the diverse and often astonishing adaptations found in the natural world. If you've ever wondered how an electric eel unleashes its formidable power, you're about to dive into the remarkable cellular machinery that makes it all possible.

At a Glance: Understanding Electrogenic Cells

- Nature's Powerhouses: Electrogenic cells, or electrocytes, are specialized biological cells capable of generating significant electrical currents.

- Found in Electric Fish: Primarily found in electric eels, rays (like Torpedo), and some catfish, forming what are known as electric organs.

- Modified Muscle Cells: In many species, electrocytes are highly modified muscle cells (called electroplax) that have lost their contractile ability but gained immense electrical potential.

- Synchronized Discharge: They work by rapidly changing their membrane potential in a highly synchronized fashion, allowing them to release powerful, cumulative electrical discharges.

- Purpose: Used for predation (stunning prey), defense (deterring predators), and electrosensory navigation (detecting objects and communicating).

- Beyond the Shock: The term "electrogenic" also describes more common cellular transport processes that move a net charge across a membrane, critical for basic physiological functions.

The Spark of Life: What Are Electrocytes?

At its heart, an electrocyte is a biological cell designed for one primary purpose: to generate and store electrical charge, then release it on command. Unlike the subtle electrical signals in our nerves and muscles, electrocytes are built for brute force. These cells are typically large, flattened discs, often arranged in stacks or columns, much like a series of individual batteries.

In electric eels (Electrophorus electricus) and electric rays (Torpedo californica), these specialized cells are derived from modified skeletal muscle cells, sometimes referred to as electroplax. Over evolutionary time, these muscle cells shed their contractile proteins, dedicating their cellular machinery entirely to the generation of voltage. They lose the ability to contract but become extraordinary biological voltage generators.

How Electrocytes Work: A Cellular Circuit Board

To understand how an electrocyte generates a powerful jolt, think of it as a master of membrane potential manipulation. Every living cell maintains an electrical potential difference across its membrane, with the inside typically more negative than the outside. This is due to the differential distribution of ions (like sodium, potassium, and chloride) and the selective permeability of the cell membrane.

Electrocytes take this fundamental principle to an extreme. Here’s the simplified process:

- Resting State: In their resting state, electrocytes maintain a polarized membrane, often with a significant negative charge on the inside. This is largely maintained by ion pumps, like the Na+/K+ ATPase, which actively transports 3 Na+ ions out of the cell and 2 K+ ions into the cell for every ATP molecule hydrolyzed, creating a net positive charge translocation out of the cell, making it electrogenic.

- Asymmetric Ion Channels: The key to an electrocyte's power lies in the asymmetric distribution of voltage-gated ion channels on its two surfaces. One side (the innervated face) is packed with sodium channels and receives nerve signals, while the other (the non-innervated face) has different channel populations.

- Neural Trigger: When an electric fish decides to deliver a shock, a signal originates from its brain and travels down specialized nerves to the electrocytes. At the electromotor synapse, neurotransmitters like acetylcholine are released. This acetylcholine-mediated transmission, observed in Torpedo marmorata as early as 1939, is crucial. The Electrophorus electric organ alone can have billions of these identical acetylcholine-containing synapses.

- Depolarization and Ion Flux: The neurotransmitter binds to receptors on the innervated face of the electrocyte, causing a rapid influx of positively charged ions (primarily sodium) through voltage-gated channels. This causes a sudden and dramatic depolarization (a reversal or reduction of the membrane potential) on that specific side.

- Unidirectional Current Flow: Because the non-innervated face has different properties (e.g., fewer or different types of ion channels that remain relatively impermeable during depolarization), the electrical current flows predominantly in one direction across the cell. This creates a powerful electrical gradient across the electrocyte itself.

- Massive Synchronization: The true power comes from the synchronization. Thousands to millions of electrocytes are arranged in series (like batteries stacked end-to-end) and in parallel (side-by-side) within the electric organ. When triggered simultaneously, the small voltage generated by each individual electrocyte adds up. A single electric eel can have thousands of these cells, collectively producing hundreds of volts and several amperes of current. To understand how eels generate electricity requires appreciating this complex, synchronized cellular orchestra.

The Broader Meaning of "Electrogenic" in Physiology

While electrocytes are specialized cells, the term "electrogenic" has a broader meaning in physiology, referring to any transport process that results in the net movement of charge across a biological membrane. This is fundamental to countless cellular functions, not just the shocking capabilities of electric fish.

- Ion Channels: Many ion channels, like those for Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Cl−, are electrogenic. When they open, they allow specific ions to flow down their electrochemical gradients, thus moving net charge across the membrane. This is crucial for nerve impulses, muscle contraction, and maintaining cellular homeostasis.

- The Na+/K+ ATPase: As mentioned earlier, this vital pump is electrogenic. For every ATP molecule it hydrolyzes, it transports 3 Na+ ions out of the cell and 2 K+ ions into the cell. This uneven exchange results in the translocation of one net positive charge out of the cell per cycle, contributing to the cell's resting membrane potential.

- Secondary Active Transporters: Many of these also qualify as electrogenic. A prime example is the Na+/glucose cotransporter found in your small intestine and kidney tubules. This transporter moves 2 Na+ ions and 1 glucose molecule into the cell across the plasma membrane. Because two positive charges (from Na+) move inward per transport cycle, it's an electrogenic process, crucial for nutrient absorption.

These fundamental electrogenic processes are the building blocks upon which the specialized electrocytes have evolved, demonstrating nature's ability to repurpose and amplify existing cellular mechanisms.

Masters of the Current: Organisms with Electrogenic Cells

The most famous examples of organisms wielding electrogenic cells are, without a doubt, electric fish. These fascinating creatures span a wide range of aquatic environments and have independently evolved electric organs multiple times, showcasing the fascinating evolution of electric organs.

- Electric Eels (Electrophorus electricus): Perhaps the most well-known, these South American freshwater fish can generate up to 600 volts, sometimes even 860 volts, in powerful bursts. Their electric organs take up a significant portion of their long bodies, consisting of thousands of electrocytes arranged in series to maximize voltage.

- Electric Rays (Torpedo californica, Torpedo marmorata): These cartilaginous fish, found in marine environments, possess kidney-shaped electric organs located on either side of their heads. Their shocks, while typically lower in voltage than an eel's (around 50-60 volts), can deliver a substantial current, enough to stun prey or deter predators. Ancient Greeks and Romans even used electric rays therapeutically for pain control, unknowingly leveraging the bioelectrical principles studied centuries later.

- Electric Catfish (Malapterurus electricus): Native to African rivers, these catfish possess an electric organ derived from modified glandular tissue rather than muscle. They can produce shocks of up to 350 volts.

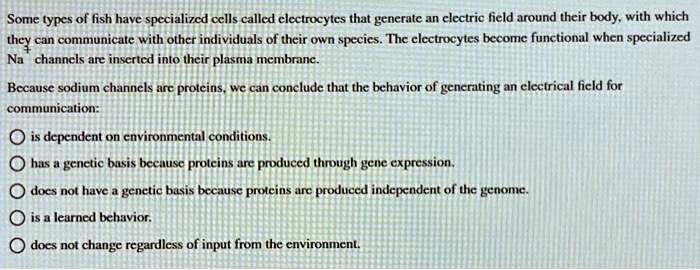

- Mormyrids (Elephantnose Fish) and Gymnotids (Knifefish): These fish use weaker electric fields for electrosensory perception and communication rather than stunning. Their electrocytes generate low-voltage discharges that create an electric field around their bodies, allowing them to navigate, locate prey, and identify conspecifics in murky water.

The Purpose of the Zap: Functions of Electric Organs

The powerful discharges generated by electrogenic cells serve several critical functions for these organisms:

- Predation: The primary and most dramatic use is to stun or kill prey. A sudden, high-voltage shock can incapacitate smaller fish or invertebrates, making them easier to catch and swallow. This is particularly effective in environments where visibility is poor.

- Defense: Electric shocks are a potent deterrent against predators. A sharp, unexpected jolt can send even large predators like caimans or sharks reeling, buying the electric fish time to escape.

- Navigation and Electrolocation: For fish that generate weaker electric fields (like mormyrids), these fields act like a biological radar. Disturbances in the electric field, caused by nearby objects or other organisms, are detected by specialized electroreceptors on their skin. This allows them to "see" in the dark, navigate complex environments, and locate hidden prey or mates.

- Communication: Weak electrical discharges can also be used for communication between individuals of the same species, especially for signaling territorial boundaries, identifying gender, or during courtship rituals.

A Historical Perspective: Unraveling Bioelectricity

The existence of electric fish has fascinated humanity for millennia. The therapeutic use of electric rays by Ancient Greeks and Romans highlights early, albeit unscientific, engagement with bioelectricity. However, it was the pioneers of bioelectricity and electrophysiology who truly began to uncover the mechanisms behind these living dynamos:

- Luigi Galvani (1737–1798): His experiments with frog legs contracting in response to electrical sparks laid the foundation for understanding "animal electricity" and the electrical nature of nerve impulses.

- Alessandro Volta (1745–1827): Inspired by Galvani, Volta developed the voltaic pile – the first true battery – demonstrating that electricity could be generated chemically, but also recognized the similarities between his artificial battery and the electric organs of fish.

- Emil Du Bois-Reymond (1818–1892): A student of Johannes Müller, Du Bois-Reymond further solidified the understanding of bioelectricity, demonstrating the electrical currents associated with nerve and muscle activity.

These early investigations, often using the electric organs of Torpedo rays and Electrophorus eels as natural models, provided crucial insights into the electrical nature of life itself. The electric organ of Torpedo became an invaluable source for studying nicotinic acetylcholine receptors due to its abundance of identical synapses and receptor protein. This provided a natural laboratory for understanding neurotransmitter release mechanisms in a highly amplified system.

The Intricate Anatomy of Electric Organs

The efficiency of an electric shock isn't just about individual electrocytes; it's about their collective organization. Consider the intricate anatomy of electric eels. Their electric organs are marvels of biological engineering:

- Arrangement in Series: Electrocytes are typically stacked in long columns, much like cells in a battery. When each cell contributes its small voltage (e.g., 0.1-0.15 volts), stacking thousands in series allows the voltages to add up, resulting in hundreds of volts across the entire column.

- Arrangement in Parallel: Multiple columns of electrocytes are then arranged in parallel. This arrangement multiplies the current output. If each column produces a certain amount of current, having many parallel columns increases the total current that can be delivered in a shock.

- Specialized Innervation: Each electrocyte is exquisitely innervated, ensuring that all cells in a column receive the neural signal to depolarize almost simultaneously. This synchronized discharge is absolutely critical; even a slight delay in a few cells would significantly diminish the overall voltage and current.

This sophisticated architectural design allows for the generation of both high voltage and high current, tailored to the specific needs of the organism – whether it's a stunning blow or a subtle navigational pulse.

Beyond the Jolt: Electrocytes and Human Applications

The study of electrogenic cells isn't just about understanding peculiar fish; it holds profound implications for human science and technology.

- Biomedical Research: The electric organ of Torpedo and Electrophorus has been a goldmine for neurobiology research. The high concentration of neurotransmitter receptors (like the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor) made it an ideal model system for studying receptor structure, function, and pharmacology. Understanding these receptors is critical for developing drugs for neurological conditions.

- Bio-inspired Robotics: Engineers are drawing inspiration from electric fish to design robots capable of sensing their environment using electric fields, particularly useful for underwater exploration in low-visibility conditions.

- Power Generation and Energy Storage: While still largely theoretical, the efficiency with which electric fish convert chemical energy into electrical energy could inspire new approaches to battery design or even biological power sources. Imagine advancements in bioelectricity for medical applications, from tiny implantable devices powered by our own body chemistry to novel ways of sensing and interacting with biological systems.

- Understanding Neurological Disorders: By studying the precise ion channel dynamics and synchronized firing in electrocytes, researchers gain a deeper understanding of fundamental electrical processes in the brain and nervous system, offering clues to disorders involving channelopathies or synaptic dysfunction.

Common Questions About Electrogenic Cells

You might be wondering about some practical aspects of these amazing cells.

Q: Can a human generate enough electricity to shock someone?

A: No, not in the way an electric fish does. While our bodies use electricity for nerve impulses and muscle contractions, the voltage and current are minuscule and internally directed. We lack the specialized electrocytes and the organized electric organs to generate an external shock.

Q: Are all fish that generate electricity equally dangerous?

A: No. The danger varies greatly depending on the species. Electric eels and large electric rays can deliver very powerful, potentially incapacitating or even fatal shocks to humans. Others, like the elephantnose fish, produce very weak fields for sensing and communication that are harmless.

Q: How do electric fish avoid shocking themselves?

A: Electric fish possess several adaptations to protect themselves. Their vital organs are often insulated by fatty tissues or are located far from the electric organ. They also have specialized physiological mechanisms that make their nervous systems and muscles resistant to their own discharges. However, a prolonged, continuous shock could still potentially harm them, which is why their discharges are typically brief bursts.

Q: Do electric fish "run out" of electricity?

A: Yes, eventually. Generating electricity consumes a tremendous amount of metabolic energy (ATP). While they can deliver many shocks, continuous, high-intensity discharges will deplete their energy reserves, requiring them to rest and refuel. Their capacity to shock is finite and dependent on their physiological state.

The Unseen Power: Where Biology Meets High Voltage

The electrogenic cells of electric fish are more than just a biological curiosity; they are a profound illustration of evolution's ingenuity. From the fundamental electrogenic transport processes that define basic cellular life to the specialized, high-voltage discharges of electric organs, the mastery of electricity is a cornerstone of biological complexity.

As we continue to unravel the intricate mechanisms of these living batteries, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for the natural world but also invaluable insights that could spark the next generation of biomedical breakthroughs and bio-inspired technologies. The silent, unseen power of electrocytes continues to inspire, reminding us that nature often holds the most electrifying secrets.